If the British and the Americans can be people separated by the same language, then what are we to make of reading graphic novels in a language other than your own? How common is the visual language of comic storytelling?

If the British and the Americans can be people separated by the same language, then what are we to make of reading graphic novels in a language other than your own? How common is the visual language of comic storytelling?It is an intriguing proposition to explore, given all the work that I’ve done in the blog over the years discussing storytelling, as I’ve been loaned a number of graphic albums recently. All in French; none of which, to my knowledge, having ever been translated into English at any point, leaving me with an experiment. How much to gleam from the storytelling alone, from the visuals, the character designs?

Up for discussion today is Orbital by Pelle and Runberg, Lupus Vol.1 by Frederik Peeters and Sambre by Yslaire and Balac. Peeters, of course, authored the brilliant Blue Pills that I reviewed years ago here, and still think fondly of (given that I believe that I loaned my sister in law my copy and I don’t think that it ever came back to me, but that’s a quibbling point). The other writers and artists are unknown to me. And I fully admit hating to type that sentence. Because I love this medium, and like most Americans I find myself provincially mired in the American comics scene, when there is a whole world of astonishing artists with which to explore.

So, without speaking a word of French, what can we take from the reading of these stories? Both a little and a lot, and much of that comes from embracing the different: different art styles, different story pacing, and different levels of imagination. Lets start with the last one first.

So, without speaking a word of French, what can we take from the reading of these stories? Both a little and a lot, and much of that comes from embracing the different: different art styles, different story pacing, and different levels of imagination. Lets start with the last one first. From the very beginning I believe that the American comic book was constrained by three things: the criminal low class with which the books were produced, the format that they were presented in, and the success of Superman. At the very onset of cheap reproduction, the pulps were overtaken by the one thing that comics needed, a hit. And a hit that would codify the way that comics were perceived (low budget crap with poor art and poorer stories), the format in which they were presented (short chapters that easily fit into a defined page count for a periodical), and that they presented a powerful nostalgia factor (kids reading Superman would want to go on and create “their” Superman for fun and profit (and, it turns out, litigation)). Super heroes would dominate most of the American market for the next 90 years. The Europeans, with a longer tradition of art and storytelling magic would produce Nosferatu to our Dracula, and years later Lt Blueberry to our Two Gun Kid. There is no way to measure the seismic difference between those books.

From the very beginning I believe that the American comic book was constrained by three things: the criminal low class with which the books were produced, the format that they were presented in, and the success of Superman. At the very onset of cheap reproduction, the pulps were overtaken by the one thing that comics needed, a hit. And a hit that would codify the way that comics were perceived (low budget crap with poor art and poorer stories), the format in which they were presented (short chapters that easily fit into a defined page count for a periodical), and that they presented a powerful nostalgia factor (kids reading Superman would want to go on and create “their” Superman for fun and profit (and, it turns out, litigation)). Super heroes would dominate most of the American market for the next 90 years. The Europeans, with a longer tradition of art and storytelling magic would produce Nosferatu to our Dracula, and years later Lt Blueberry to our Two Gun Kid. There is no way to measure the seismic difference between those books.

So what can we take away from those books? That the French are utterly, astonishingly, so much less fettered in their imagination that even when working on very familiar ground they inject freshness into the story. Sambre appears to be a love story between a young, depressed nobleman and a beautiful vampire. The middle third contains one long intercut seduction/sex scene in a crypt that is gorgeously drawn and staged. Orbital looks to have a future Earth being invaded by dark spider/insect aliens and the drama of the rag-tag interstellar who will have to learn to work together to save the planet.

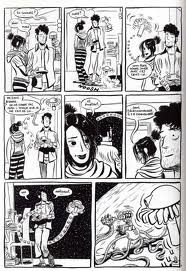

So what can we take away from those books? That the French are utterly, astonishingly, so much less fettered in their imagination that even when working on very familiar ground they inject freshness into the story. Sambre appears to be a love story between a young, depressed nobleman and a beautiful vampire. The middle third contains one long intercut seduction/sex scene in a crypt that is gorgeously drawn and staged. Orbital looks to have a future Earth being invaded by dark spider/insect aliens and the drama of the rag-tag interstellar who will have to learn to work together to save the planet.Lupus? I have no idea what the fuck is going on. Other than it appears that Peeters doesn’t own a pencil and simply goes straight to ink on every panel that he draws. The wet, inky boldness of his drawing both sucks me in and makes the book appear to have simply appeared from his sketchbooks as opposed to the intricate work in Sambre and Orbital.

There is more design imagination in the construction of the Orbital architecture than in the last 12 issues of Fantastic Four and X-Men. And, yes, there are certainly echos of McKie, and Alien and Blade Runner and the Rebel Alliance but who cares? Even working the interstellar troops trope the books crackles with conviction

Next up: thoughts on how the page count and page size contributes to the storytelling experience (and differences therein). Not to mention the revelation that men have penises during sex scenes.